Saramat

| Allegiance | Sirdabi Caliphate |

| Capital | Sibela |

| Governor | Hashem bin Najjari Bey |

| Demonym | Sarmati |

| Official Language | Sirdabi |

| Official Religion | Azadi |

| Currency | fals/dirham/nour |

| Native Heritages | Sirdabi, Irzali |

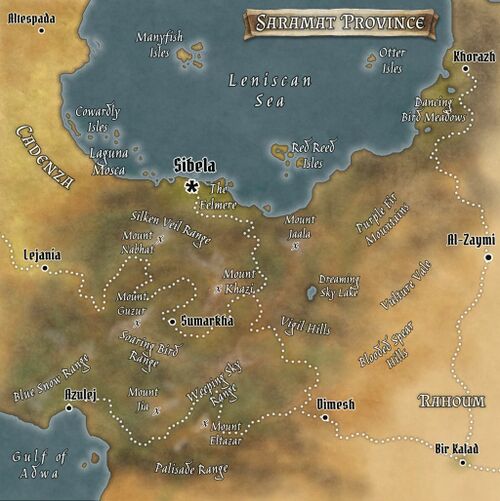

Saramat is a border province of the Sirdabi Caliphate, lying to the northwest of the Sirdabi homeland of Rahoum. With the exception of a few marshy pockets along the Leniscan coast and the arid plain around al-Zaymi, the province is dominated by lofty mountain ranges of challenging terrain and weather, navigable only via equally challenging passes. Its native people, the tribal Sarmatiyyans, serve as vigorous yet often wayward guardians of the Kalentoi frontier, while a small population of Sirdabi administrators struggle with the demands of both empire and climate.

Geography

Saramat shares its western border with Cadenza, a part of the Kalentoi Empire, and is bounded on the north by the Sea of Lenisca and on the south by the Gulf of Adwa. The landscape consists almost entirely of high mountains and steep valleys, woven through with narrow and often treacherous passes, which blur into the equally mountainous country of Irzal to the northeast. South and east the mountains fall away into foothills, eventually merging with the desert plain that marks the boundary with Rahoum.

The great al-Khazi range forms the heartland of the province, where the tallest snow-capped peaks seem to pierce the sky. As the meeting place of multiple streams of moisture flowing off the Gulf of Adwa and Leniscan Sea, the al-Khazi is frequently overcast and wet, the pinnacles themselves often becoming lost in heavy curtains of cloud, or veiled by misty rains. In the winter the precipitation is less, but the start of the season -- which may come as early as Kholabi -- is typically marked by a period of intense snows that blanket the entire region and render the trails through the heights impassable. But this heavy burden of precipitation is also a gift, responsible for clothing the coastal slopes with a thick tall growth of evergreen trees, while the valleys and plateaus of the uplands offer enviably rich and verdant pasturage in the warmer months of the year.

The Purple Fir Mountains of eastern Saramat are overall lesser in height with fewer prominent peaks, though the general elevation increases heading northeast into Irzal. They are also much drier and generally warmer as well, so that the Sarmatiyyan sheepherders often pasture their flocks here during the winter. These mountains support not only the purple firs that give them their name, but also oak and goldencrown trees growing in small open woodlands intermixed with larger expanses of open grass. As along most of Saramat's Leniscan coastline, the mountains meet the sea very steeply in most places, leaving little in the way of beach. One of the few exceptions is the expansive Dancing Bird Meadows at the Leniscan's southeast corner, which in fact is more marshland than meadow. This lush wetland provides the mountain Sarmatiyyans' lake-dwelling kin with plentiful fish and game, as well as wild rice and tubers, and the sand bars closer to the sea itself offer mussels and crabs as well.

A slender strip of equally marshy land known as the Eelmere is one of the few other level places in the entire province, and the only one connected by road to the rest of Saramat or the greater caliphate. Despite the wishful thinking of Sirdabi administrators, however, the boggy area is poorly suited to any form of agriculture except rice growing, and the local tribes are perennially disinclined to buckle down to the demands of production farming. The provincial capital of Sibela remains more of an administrative outpost than anything resembling the sophisticated Sirdabi ideal of a city, and most Sirdabi officials consider any posting to Saramat a misfortune merely to be endured.

People

The population of Saramat consists chiefly of people of Sirdabi heritage, a mix of local tribes who have resided in the region for generations and more recent settlers from other parts of the caliphate. Most of the latter live in the provincial capital of Sibela, or in the foothill towns of Dimesh and al-Zaymi. There they man the provincial administration and find employment as traders, crafters, farmers, and other professions in which the native tribes take vanishingly little interest.

The native residents of Saramat are the seminomadic pastoralists known collectively as the Sarmatiyya. They are primarily descended from Rahoumi tribesmen who presumably migrated out of the desert some forgotten number of generations ago. The Sarmatiyya were once allies of the Kalentoi, helping to guard the frontier against attack from the east by the rival Irzali Empire. However, relations between the Sarmatiyya and the Kalentoi soured after 56 BD, when Emperor Milentos chose to stop paying the tribes tribute for their services in safeguarding the border. This eventually led to the tribes quietly allowing passage to the enemies of the Kalentoi -- first to Irzali raiding parties, and ultimately to the armies of Sirdab in the days of the Azadi conquests. Capable of holding a grudge for generations, the Sarmatiyya still harbor a profound contempt for the Kalentoi.

They are not overly fond of their new rulers either, for despite being ethnically Sirdabi themselves they feel virtually no kinship for those Sirdabi who have embraced the Azadi faith. The Sarmatiyya still venerate the old gods and spirits -- nature deities, ancestral clan spirits, and other such entities -- and they do not forgive the desert Sirdabi for having chosen to throw the various material foci for such worship out of the ancient Sirdab shrine in Rahoum. On account of this desecration, the Sarmatiyya refer to Azadi Sirdabi as "the Godkillers". But this is a term more of mockery than anger, since the Sarmatiyya find it patently ridiculous that the Azadi believed they could destroy the gods simply by throwing out their ritual objects from the ancient shrine. The mountain tribesmen believe that following this act the gods simply abandoned the Sirdabi and came to live in Saramat with the Sarmatiyya instead, who call themselves the Friends of the Gods.

The Sarmatiyya are given to raiding one another on horseback and rustling livestock, and some bands also prey on unwary travelers through the mountain passes, rendering both trade and travel difficult. Such depredations are a perpetual thorn in the side of the provincial administrators, tasked as they are with maintaining the peace and keeping trade routes open. However, some of them develop a grudging respect for the Sarmatiyyans' courage and daring, and few will deny the benefits of having such a pugnacious people to guard the northwestern border of the caliphate.

Although the mountain-dwelling Sarmatiyyans have by far the greater fame, other tribes live among the islands of the Leniscan Sea and ply their reed boats skillfully across its waters. Primarily fishers, they also hunt the waterfowl of the marshes and gather wild plants from both island and shore. Although generally more peaceable than their mountain kin and willing to allow travelers unhindered passage across the sea, they are resentful of any interference or encroachment upon the islands they consider their home and can be as ferocious as any other Sarmatiyyan tribe when crossed.

Besides these Sirdabi peoples, Irzali heritage is widespread in the northeastern part of the province, particularly in the town of Khorazh. In Azulej, tucked on the south side of the mountains on the Gulf coast, a very diverse mix of people from around the Adelantean and even the Sea of Sala'ah can be found. Finally the western garrison town of La Lejanía is populated largely by mizados of mixed Sirdabi and Cateni heritage.

Economy

Despite its minimal arable land and general dearth of manufactures, Saramat occupies a vital place in the economy of the caliphate. Besides providing some of the realm's hardiest soldiery in the form of Sarmatiyyan merceneries, Saramat furnishes a wide array of natural resources that provide Sirdabi towns and cities with raw materials for numerous domestic industries.

Timber is one of the most important resources of the province, as the wetter coastal mountainsides are covered thickly with Sarmatiyyan pine, blue spruce, starcedar, and other commercially valuable tree species. Pine in particular is essential for providing masts and pitch for shipbuilding, while starcedar and prickly cedar furnish an abundance of durable rot-resistant planking. The waxy bluish cones of starcedar are also used in the production of starshine, a gin-like beverage which is drunk locally by the Sarmatiyyans (and more discreetly by fraught Sirdabi officials) as well as being exported to Kalentoi lands.

Mining is another extremely important part of the economy. Copper, iron, and saramite are all mined here, with some mines also having deposits of semiprecious stones such as carnelian and malachite. Although the caliphate's first mining ventures attempted to make use of the labor of local tribes, these proved so hostile to the work and displayed such a strong propensity to vanish back into the mountains that a different source of labor was required. As a result, the modern-day mining workforce is made up largely of convicts from around the caliphate and slaves taken in battle. Although the Sarmatiyyans tend to have little but contempt for most of these laborers, occasionally they find enough sympathy for pagan Jadniek slaves that these likewise sometimes disappear into the wilderness, much to the exasperation of Sirdabi overseers.

In addition to semiprecious stones, other luxury exports from Saramat include furs and fleece. The Sarmatiyyan herders' Khazi mountain sheep grow unusually long and luxuriant coats that can be spun into a superbly soft and weatherproof yarn, while the creature's dense undercoats make an equally fine and durable felt. So-called "alkhazi" fabrics are highly prized both within the caliphate and beyond, wherever the winter weather tends to cold and damp.

Religion

Azadi is the official religion in Saramat as in all Sirdabi lands, but it has not been embraced by the local Sarmatiyyan population. These by and large cling stubbornly to their ancestral pagan faith, with its expansive assortment of local gods and spirits. As noted above, many of these deities are those which the tribes originally worshipped in Rahoum, but besides these the Sarmatiyyans have adopted still other gods considered native particularly to the mountains -- the aboriginals of the local spirit world. Many mountain peaks bear the names of the gods, each one believed to be the special haunt of that particular deity. Khazi, the great sky god, has given its name to both to the central mountain range as a whole and to the tallest peak in it.

Shamanism is central to Sarmatiyyan spiritual life, and those who are born with a strong connection to the supernatural are greatly honored and respected. Both men and women may become great shamans, though women generally are discouraged from devoting themselves to this path until after their childbearing years. Shamans are responsible for communing with, beseeching, and appeasing the numerous gods, and for leading the communal rituals that demonstrate the Sarmatiyyans' friendship with the gods and guarantee their good favor. Dreaming Sky Lake and the valley it rests in are one of the most sacred spaces of the Sarmatiyyans, and outsiders who enter the valley risk a merciless death if they are discovered.

Among the more unusual deities of the local tribes are the bear spirits. The blue, or man-walking, bear, is revered and considered a special guardian and spirit helper allied with the goddess Jia. While it sometimes preys on young lambs, rather than begrudging these losses the Sarmatiyyans view them as offerings to the blue bear, which in turn is expected to defend the tribes against greater threats. The stalking bear, in contrast, is an object of the most profound dread, being seen as the creature of Guzur, the great death spirit. While other local animals and plants are associated with their own spirits or gods, none provoke quite such strong feelings as the two mighty bears of the mountains.

Although it is unusual, a few Sarmatiyyans have embraced the faith of the Sirdabi newcomers and become devout Azadi, following the daily prayers and even constructing the occasional small mosque or shrine for worship. Despised by their pagan kin, most of these converts have given up their nomadic lifestyle to reside year-round in the enclave of Sumarkha in the central mountains, or have found work in the provincial capital of Sibela.

Cities & Towns

- Sibela, the marshy and not-infrequently malarial provincial capital.

- Al-Zaymi, a resilient and resourceful fortress town situated on one the most battle-torn plains of Ruleska.

- Azulej, a picturesque and multicultural harbor town overlooking the Gulf.

- Dimesh, called Bab al-Khazi, the Gateway to the al-Khazi Mountains, and home of one the great livestock fairs of the caliphate.

- Khorazh, a largely Irzali market town nestled at the mouth of the Flaming Heart Gorge.

- Lejanía, a mizado garrison town, equally equipped for battle and barter with their Cadenzan neighbors.

- Sumarkha, the traditional summer encampment of the Sarmatiyya, now also a rustic Sirdabi administrative outpost.